Feeling brave in Tokyo? Perhaps you want to try chowing down on fugu? Or standing toe-to-toe with a sumo? Or maybe just doing a spot of recycling.

It should be no surprise that the place that spawned a New York Times best-seller dedicated to the art of tidying up should have an astonishingly elaborate system for sorting its garbage. Not content with broad categories of recycling, Japan asks people to sift categories of waste into an elaborate dichotomy that requires a diligent household to have up to a dozen piles, lest the juice cartons contaminate the miso boxes, or the plastic bento trays interfere with the empty drink bottles.

Sorting through garbage has become part of the Japanese experience. Where many other parts of the world cluster recyclable things together when they leave the home, and only sort things downstream, Japan has opted to put the burden firmly on the shoulders of individuals.

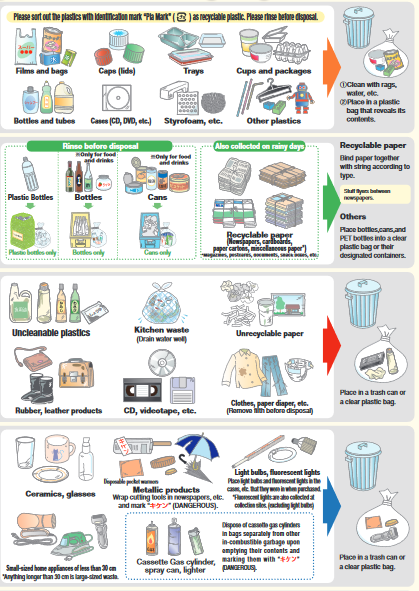

The information sheet issued by the ward administration in our part of Tokyo does a heroic job of explaining the different categories into which trash must be sorted.

So what are the Dirty Dozen? There’s glass, cans, plastic bottles, other plastic, newspaper, cardboard, drink cartons, books and magazines, batteries, rags – and then whatever doesn’t fit into these categories is separated into burnable or non-burnable. Got all that?

Adding to the complexity is the schedule of garbage collection, in which different categories are collected on different days, sometimes with differing frequency. It is little wonder that one of the objections some locals have to Airbnb leases in their neighbourhood is that non-locals will not follow the garbage disposal rules properly.

And things don’t get much easier when you leave the house. Public bins are scarce in parks and at railway stations, so people are expected to carry their garbage until they find a suitable spot to dispose it, or a sufficiently discreet enough spot that they can leave it without fear of discovery.

When you do finally find a recycling station, they look a bit like this:

Self-serve restaurants expect patrons to sort out their leftovers in garbage at elaborate disposal stations, prompting each patron to form a snap judgement about the combustibility of each item on their tray, haunted by the social opprobrium that may be directed their way should they make a bad call.

The success of the Japanese system relies on a strong popular willingness to comply. Sorting garbage is tricky, messy and time-consuming. It relies not only on most people knowing the rules – which itself depends on good communications and high rates of literacy – but also on caring about the rules.

An ingrained commitment to rules and confidence in the fairness of the system is needed to achieve such a high rate of compliance, all the more so when the act of sorting garbage is basically private, involving only the sacred bond between trash-chucker and garbo.

In public places, people in many parts of the world have come to expect an abundance of easily accessible bins. Take those bins away, or make them complex to use, and some people believe they have been relieved of their obligation to clean up after themselves.

And yet, in Japan it works: the streets are spotlessly clean, non-compliance is rare and recycled materials are commonplace. In fact, it has helped turn Japan into a global leader in recycling strategy, prompting others around the world to consider if they can take a leaf from Japan’s book.

It is tricky to find good data on how countries compare in their trash habits, but some World Bank numbers look pretty good for Japan. Japan generates 1.71 kilos of municipal solid waste per person per day, less than most other developed countries including Australia (2.23 kilos), Germany (2.11 kilos) and the United States (2.58 kilos). And in sending just 3 per cent of its total waste to landfills, it is one of the lowest the world.

Curiously, 74 per cent of its total waste is reportedly used in energy production. There’s an excellent explainer on that – and more – over at Tofugu:

If you hear the words “fluidized bed” in relation to Japan, you might think you’re reading an article about Love Hotels. Sorry to disappoint, but at least fluidized bed combustion is pretty exciting. It is a very efficient way of burning materials that don’t normally burn easily. Your carefully sorted rubbish will be suspended in a hot, bubbling bed of ash and other particulates as jets of air are blown through it. Apparently the “fast and intimate mixing of gas and solids promotes rapid heat transfer and chemical reactions within the bed.” Who ever said garbage disposal wasn’t sexy?

All joking aside, this thermal treatment of municipal solid waste does have some advantages over other forms of incineration. It is cheaper, takes up less space, and produces fewer nitrogen oxides and less sulphur dioxide. One of them was even built near Shibuya station in 2001. It can also be used as part of a Waste to Energy system, using the resultant heat to create power.

What has promoted Japan to take such a zealous approach to recycling? As the saying goes, necessity is the mother of recycling – or something like that. A report from the Institution of Environmental Sciences pinpointed three reasons why Japan has become a leader:

- High population density and limited landfill space;

- Very limited domestic metal and mineral resources, making remanufacturing and recycling attractive;

- A business culture emphasising collaboration, leading to a comprehensive approach, both to measurement and to action.

There is one piece of the puzzle, though, that Japan has largely ignored: reducing consumption.

Japan has fetishised packaging on consumer products to such an extent that even the simplest of products has an elaborate unboxing process that would make the most narcissistic YouTuber salivate.

Take these two apples, for sale recently at a Tokyo supermarket. The apples themselves – robust fruit that could probably fend for themselves pretty well – were resting in pink beanies, sitting on a paper tray, surrounded in a plastic wrap and then labelled, as if their apple-ness was not immediately apparent.

It seems that the packaging here serves far more of a symbolic, rather than practical, function: the packaging is connoting the pristineness of the product, its separation from the wild, untamed (and, yes, dirty) natural world from which it is sourced. In other contexts, the packaging acts as a symbol of thoughtfulness, of a gift or of effortless affluence.

Take these well-packaged items to the cash register and you will almost always be offered a plastic bag in which to place them. Bring your own bag to the counter, or seek to go bag-free, and you will get the same quizzical look from the attendant as if you had just rocked up with a parrot perched upon your shoulder, a look that says “That’s not how we do things around here.”

At first glance it seems odd for a culture that takes such pride in its recycling to have so few qualms about superfluous consumption and packaging. But perhaps the recycling is used to excuse the wasteful packaging, allowing people to continue to accept layer upon layer by giving them the psychological comfort that the waste will eventually be recycled. In that way, the elaborate recycling rituals may act as an enabler for wasteful behaviour among people who just cannot bear to give it up.

This is not to say that winding back the recycling effort would force a rethink of packaging habits. It seems these excessive packaging habits are largely ingrained and will not change easily. An interesting parallel can be seen in the efforts to reduce electricity consumption in the wake of the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 2011, which put Japan’s nuclear power industry offline. For the summer that followed, offices switched off their air conditioning, shopping malls switched off their escalators and izakayas switched off their neon, cutting demand by up to 20 per cent in some places. Did this newfound austerity last? By the time I visited in the summer of 2012, things had pretty much returned to normal and have stayed that way. Some habits are too hard to break.

Japan’s commitment to recycling is impressive, and sets a benchmark for the rest of the world. Couple that with reduced consumption, though, and the results could be even better.

Keen for more trivia on trash in Japan? Check out this excellent collection.